The Traditional GIL (Pre-3.13)

In Lesson 1, you learned that CPython uses reference counting to manage memory—each Python object tracks how many references point to it. In Lesson 2, you explored performance optimizations that make CPython faster.

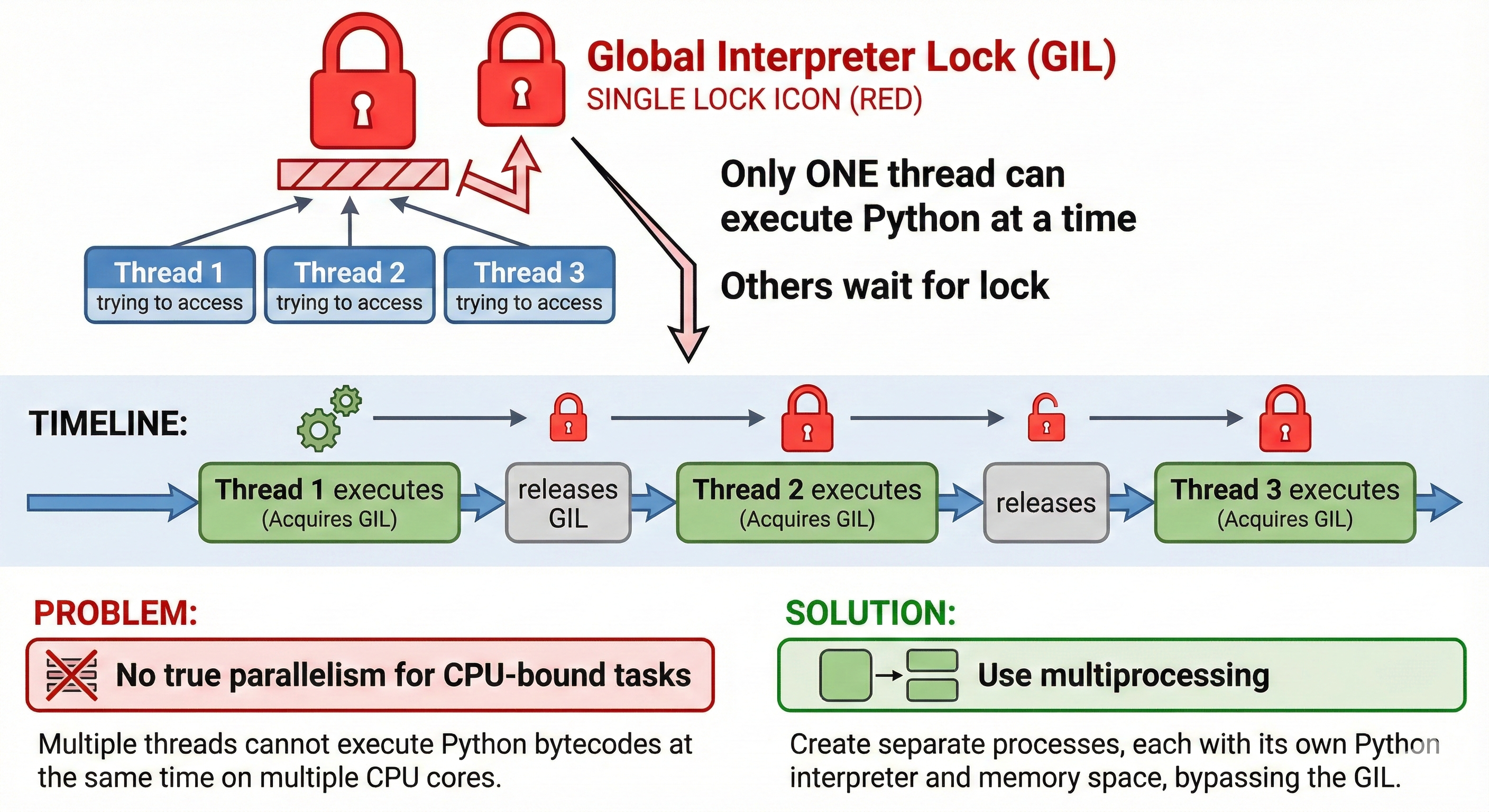

Now comes the big constraint that shaped Python for 30 years: the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL).

The GIL is a mutual exclusion lock (mutex) that protects CPython's interpreter state. Only one thread can execute Python bytecode at a time, even on multi-core hardware. This single design choice prevented true parallel threading in Python for three decades.

In this lesson, you'll understand:

- What the GIL is and why it exists

- The critical distinction between CPU-bound and I/O-bound workloads

- Why threading works for one but not the other

- How multiprocessing and C extensions work around the limitation

Why this matters: Concurrency strategy is the highest-leverage decision in system design. Choosing the wrong approach wastes developer time and computing resources. Understanding the GIL and workload classification is how you make the right choice.

Section 1: What is the GIL?

The Basic Definition

The Global Interpreter Lock is a mutex (mutual exclusion lock) that protects CPython's interpreter state. Think of it like a single-user license for a room: only one thread can hold the lock and execute Python bytecode at a time.

Timeline with multiple threads:

Thread 1: [Holds GIL, executes bytecode] → [Releases GIL] →

Thread 2: [Holds GIL, executes bytecode] →

Thread 3: [Holds GIL, executes bytecode]

Result: Threads take turns, never truly parallel

Every Python bytecode instruction is preceded by:

- Check if I own the GIL

- Execute instruction

- Periodically release GIL so other threads can run

The GIL makes multithreading look like it works (threads do take turns), but it prevents true parallel execution.

Why the GIL Exists: Reference Counting Safety

To understand WHY the GIL is necessary, you need to understand CPython's memory management challenge.

The Problem: CPython uses reference counting, which means every object tracks "how many references point to me?"

Loading Python environment...

The Thread Safety Problem: Reference counting isn't thread-safe without synchronization:

Thread A: Reading ref count = 2

Thread B: Incrementing ref count = 3

Thread A: Decrementing based on old read = 1 (BUG! We lost an increment!)

Result: Incorrect ref count, premature memory release, crashes

The Simple Solution: Protect ALL reference counting with a single lock. That's the GIL.

Thread A: [Owns GIL] Read ref count = 2 → [Released GIL]

Thread B: [Owns GIL] Increment ref count = 3 → ...

Result: Thread-safe reference counting (but only one thread at a time)

💬 AI Colearning Prompt

"Ask your AI: 'Explain the Global Interpreter Lock in simple terms. Why does CPython need it? What would happen if we removed it without replacing reference counting?' Then explore: 'What does "thread-safe" mean in this context? Why can't multiple threads safely modify the same ref count at the same time?'"

Expected Exploration: You'll develop intuition for why GIL was needed (thread safety), and you'll understand that it's not a malicious design choice—it was pragmatic given CPython's architecture.

Why GIL Simplifies C API (The Hidden Reason)

Here's the deeper reason GIL exists: CPython's C API.

CPython is written in C. C programmers can create Python extension modules (like NumPy, pandas) that manipulate Python objects directly from C code. Without the GIL:

// Hypothetical unsafe C extension code (WITHOUT GIL protection)

PyObject *list = PyList_New(10);

PyList_SetItem(list, 0, PyLong_FromLong(42)); // What if another thread modifies list here?

// Crashes, memory corruption, undefined behavior

With the GIL, C extension authors have a much simpler contract:

// C extension code WITH GIL guarantees

PyObject *list = PyList_New(10);

// GIL guarantee: no other thread runs Python bytecode

PyList_SetItem(list, 0, PyLong_FromLong(42)); // Safe!

This simplification is enormous. Without the GIL, every C extension would need complex thread-safety code. With the GIL, extensions just execute knowing they're protected.

🎓 Expert Insight

Here's the professional perspective: the GIL made perfect sense in 1989 when Guido van Rossum created Python. Single-core machines. No parallelism benefit possible anyway. The GIL simplified interpreter design and C API—huge wins for a language trying to be extensible and pragmatic.

The problem? 30 years later, multi-core machines are universal. The GIL became a bottleneck. But removing it without breaking C API was nearly impossible—that's why it took until 2024 (free-threading) to actually solve it.

This isn't a design mistake. It's a generational shift. Every design choice makes sense in its time. The GIL is what made CPython viable in the 1990s. Free-threading (Lesson 4) is what makes it viable in the 2020s.

Section 2: Why the GIL Exists (The Full Picture)

Let me connect the dots between reference counting, thread safety, and the C API:

Reference Counting Is Not Inherently Bad

Reference counting is elegant and simple: when ref count reaches 0, immediately free memory. No pauses for garbage collection sweeps.

Without thread safety, reference counting fails on multi-threaded code:

Time 1: Thread A checks: ref_count = 2

Time 2: Thread B increments: ref_count = 3

Time 3: Thread A decrements from OLD value: ref_count = 1 (WRONG! Should be 2)

This is a race condition—the final value depends on timing, not logic.

The GIL Is the Simplest Solution

Protect all reference count operations with a single lock:

Loading Python environment...

Cost: Only one thread executes Python bytecode at a time.

Benefit: Guarantees thread safety without needing per-object locks.

Why CPython Didn't Use Per-Object Locks

A naive alternative: give each object its own lock.

Loading Python environment...

Problems:

- Deadlock risk: If Thread A locks obj1 then tries to lock obj2, while Thread B locks obj2 then tries obj1 → deadlock

- Memory overhead: Millions of objects, each needs a lock → significant memory waste

- Complexity: Developers must reason about lock ordering and deadlock prevention

A global lock is simpler, safer, and costs less memory.

The 30-Year Design Tradeoff

In 1989: Multi-core wasn't common. Single-core machines meant GIL had zero performance cost (no parallelism possible anyway). The simplicity won.

In 2024: Multi-core is ubiquitous. GIL became a visible limitation. That's why free-threading finally happened (Lesson 4).

The moral: design choices that are optimal in one era become constraints in another. Understanding the GIL means understanding this historical context.

Section 3: CPU-Bound vs I/O-Bound (THE CRITICAL CONCEPT)

This is the most important distinction in concurrency strategy.

CPU-Bound Workloads: The GIL Prevents Parallelism

CPU-bound means your code does actual computation:

Loading Python environment...

During this task, the thread holds the GIL continuously—there's no reason to release it (no waiting for external resources).

If you create 4 threads to run this task:

Thread 1: [========== CPU work ==========] [Hold GIL the whole time]

Thread 2: [................] [Waiting for GIL] [........] [CPU work]

Thread 3: [................] [Waiting for GIL] [............] [CPU work]

Thread 4: [................] [Waiting for GIL] [..................] [CPU work]

Result: Threads take turns. No parallelism. Actually SLOWER due to context switching overhead.

Real-world CPU-bound examples:

- AI inference (transformer calculations)

- Data processing (pandas operations, NumPy matrix math)

- Prime number calculations, cryptography

- Video encoding, image processing

- Any calculation-heavy task

💬 AI Colearning Prompt

"Ask your AI: 'Give me 10 real-world examples: 5 CPU-bound tasks and 5 I/O-bound tasks in AI applications. For each, explain WHY it's CPU or I/O-bound. Include examples like transformer inference, web API calls, vector database queries, model training, file I/O, and LLM completion generation.'"

Expected Exploration: You'll build the CPU vs I/O distinction through diverse examples relevant to AI systems.

I/O-Bound Workloads: The GIL Releases During Waits

I/O-bound means your code waits for external resources:

Loading Python environment...

When a thread calls time.sleep(), it's waiting for time to pass—no CPU work happening. CPython releases the GIL during this wait:

Thread 1: [Request network] [===== GIL Released, waiting =====] [Got response] [Process]

Thread 2: [====== Executes bytecode ======] [Done]

Thread 3: [========== I/O wait ==========] [Execute]

Result: Other threads can run while this one waits. Pseudo-parallelism works!

The same timeline WITH only single-threaded approach (for comparison):

Single thread: [Request network] [===== All waiting =====] [Got response] [Process network]

[Then do other work]

With threading and I/O-bound tasks:

Main thread: [Request network] [===== Waiting =====] [Got response] [Process]

Worker thread: [Do other work] [Done]

Total time: Faster! Work done while waiting

Real-world I/O-bound examples:

- Network requests (calling APIs, fetching data)

- Database queries (waiting for query results)

- File I/O (reading/writing disks)

- User input (waiting for keypress)

- Any operation that waits for external completion

🚀 CoLearning Challenge

Ask your AI Companion:

"Tell your AI: 'Generate code that proves threading makes I/O-bound tasks faster. Create a function that simulates 5 network requests. Run it single-threaded (one at a time) and then with 5 threads (concurrent). Measure the time for each approach. Explain why threading is faster for I/O-bound work even with the GIL.'"

Expected Outcome: You'll experience GIL release during I/O; see practical speedup from concurrent I/O waiting.

The CPU vs I/O Distinction Table

Use this table to classify workloads:

| Aspect | CPU-Bound | I/O-Bound |

|---|---|---|

| What is happening | Actual computation | Waiting for external resource |

| GIL during work | Held (continuous) | Released (during wait) |

| Threading benefit | None (GIL prevents parallelism) | Yes (other threads run while waiting) |

| Best approach | Multiprocessing, free-threading, or C extensions | Threading or asyncio |

| Example | Prime calculation, AI inference | Network request, database query |

Section 4: Threading Doesn't Work for CPU-Bound

Let me show you empirically why threading fails for CPU-bound tasks.

Code Example 3: CPU-Bound vs I/O-Bound Demonstration

Specification: Create functions that show the difference between CPU-bound and I/O-bound tasks. Measure how long each takes to complete. Compare the actual execution time.

AI Prompt Used:

"Generate Python code with type hints that defines a CPU-bound task (calculate sum of squares) and an I/O-bound task (sleep for duration). Create a measure_time function that uses time.perf_counter() for accurate timing. Show execution time for each task."

Generated Code:

Loading Python environment...

Validation: This code runs on all platforms (Windows, macOS, Linux) without dependencies. CPU-bound time varies by machine speed; I/O-bound time is always ~2 seconds (the sleep duration).

✨ Teaching Tip

Use Claude Code to explore this interactively:

"Run the code above on your machine. Then ask your AI: 'Why does

time.sleep()release the GIL, but thesum()calculation doesn't? Explain what's happening in the CPython interpreter for each task.' Then modify the CPU task to use 50 million instead of 10 million and compare times."

Expected Outcome: You'll see concrete timing differences. You'll understand that sleep times are predictable (GIL released), while computation times vary with machine performance.

Code Example 4: Benchmark - Traditional Threading

Specification: Demonstrate that threading provides NO speedup for CPU-bound tasks due to the GIL. Create a benchmark that runs the same CPU task with 1 thread, 2 threads, 4 threads, and 8 threads. Measure total time for each. Show that threading actually makes it slower due to context switching overhead.

AI Prompt Used:

"Generate Python code with type hints that benchmarks a CPU-bound task with increasing thread counts. Use threading.Thread, join(), and time.perf_counter(). Run the same task with 1, 2, 4, 8 threads and measure total execution time. Add comments explaining GIL behavior."

Generated Code:

Loading Python environment...

Validation: Run this on your machine. You'll observe:

- 1 thread: baseline

- 2-8 threads: similar or slightly slower (GIL overhead dominates)

- Never a speedup (GIL prevents it)

🎓 Expert Insight

Understanding WHY this benchmark shows no speedup is more valuable than memorizing THAT it does. Here's the professional insight:

Semantic understanding: Threading creates concurrency (switching between tasks), but the GIL prevents parallelism (actual simultaneous execution). For CPU work, concurrency without parallelism is a liability—you get context switching overhead without the benefit of parallel work.

Professional approach: When you hit performance issues, you measure. You don't guess. You run benchmarks like this one, you profile with cProfile or flamegraph, and you make decisions based on data.

Section 5: Threading Works Fine for I/O-Bound

Now let's see how threading helps with I/O-bound tasks:

Why Threading Works for I/O-Bound

I/O operations release the GIL. When a thread waits for a network request, database query, or file read, it releases the GIL:

Thread 1: [GIL] Initiate I/O request → [Release GIL] Wait for response

Thread 2: [Acquire GIL] Do work → [Release GIL] I/O wait

Thread 3: [Acquire GIL] Do work ...

Result: While one thread waits, others execute. True concurrency!

The threading module automatically releases the GIL during blocking I/O operations (calls to socket operations, file reads, etc. through Python's standard library).

Real-World I/O-Bound Example: Multiple Network Requests

Without threading (sequential):

Request 1: [1ms send] → [500ms wait] → [5ms receive] Total: 506ms

Request 2: [1ms send] → [500ms wait] → [5ms receive] Total: 506ms

Request 3: [1ms send] → ...

Total: 1.5+ seconds (requests are serialized)

With threading (concurrent I/O):

Thread 1: [1ms send] → [500ms wait for response]

Thread 2: [1ms send] → [500ms wait for response]

Thread 3: [1ms send] → [500ms wait for response]

Total: ~502ms (requests happen concurrently, responses arrive while sending others)

The time saved comes from concurrency—while one thread waits, others send requests.

💬 AI Colearning Prompt

"Ask your AI: 'Show me an example where threading DOES provide speedup for I/O-bound work. Create code that makes 4 network requests sequentially vs with 4 threads. Measure the time for each approach. How many concurrent network requests can 4 threads handle? Explain why this works despite the GIL.'"

Expected Exploration: You'll understand that threading excels at I/O-bound work because GIL is released during waits, allowing true concurrency.

✨ Teaching Tip

Here's how to develop intuition for CPU vs I/O classification in your own work:

"Ask your AI to help you classify YOUR recent projects: 'Analyze this code [paste]. For each function, is it CPU-bound or I/O-bound? What concurrency approach would you recommend? If you see threads in the code, are they helping or hurting performance?' Build this habit: before writing concurrent code, classify the workload first."

Expected Outcome: You'll develop the professional habit of workload classification BEFORE choosing a concurrency strategy. This single habit prevents most concurrency mistakes.

Section 6: CPU-Bound Workarounds in Traditional Python

Since threading doesn't work for CPU-bound tasks, Python developers traditionally had two workarounds:

Workaround 1: Multiprocessing (Separate Interpreters, Separate GILs)

The Idea: Create separate Python processes, each with its own GIL. They can run in true parallel on multiple cores.

Loading Python environment...

Advantage: True parallelism on multi-core hardware. Each process has its own GIL.

Disadvantages:

- Memory overhead: Each process duplicates the entire Python interpreter (~50-100MB each)

- Communication overhead: Sharing data requires serialization (pickle) → slow

- Startup cost: Creating processes is expensive

When to use: CPU-bound work where memory overhead is acceptable (e.g., batch processing, scientific computing)

Workaround 2: C Extensions (Release GIL in C Code)

Libraries like NumPy, pandas, and scikit-learn write performance-critical code in C. C code can explicitly release the GIL:

// Hypothetical C extension (simplified)

static PyObject* matrix_multiply(PyObject* self, PyObject* args) {

PyObject *matrix_a, *matrix_b;

if (!PyArg_ParseTuple(args, "OO", &matrix_a, &matrix_b)) {

return NULL;

}

// Release GIL for heavy computation

Py_BEGIN_ALLOW_THREADS

// C code here runs without GIL

// Can use true parallelism (OpenMP, pthreads)

float* result = multiply_matrices(...);

Py_END_ALLOW_THREADS

return create_python_array(result);

}

Advantage: True parallelism while keeping Python API.

Disadvantage: Requires writing C code (difficult) and the C code must be thread-safe (dangerous if not careful).

When to use: When you need high performance AND want to stay in Python ecosystem. NumPy uses this pattern heavily—that's why NumPy operations are so fast.

🚀 CoLearning Challenge

Ask your AI Companion:

"Tell your AI: 'Compare threading vs multiprocessing for the same CPU task. Show me the code for both approaches. Measure execution time for each. Create a side-by-side comparison: code complexity, memory usage, speed. When would I choose one over the other?'"

Expected Outcome: You'll practice decision-making between concurrency approaches; you'll see that multiprocessing trades off simplicity for true parallelism.

💬 AI Colearning Prompt

"Ask your AI: 'I have a CPU-bound AI task that needs parallelism on multi-core hardware. Should I use multiprocessing (separate processes) or C extensions (with GIL release)? Compare: setup time, memory usage, communication overhead, learning curve. When is each approach worth it?' Then explore: 'What would happen if I tried threading instead?'"

Expected Exploration: You'll practice strategic decision-making between workarounds; you'll understand the tradeoffs of each approach; you'll prepare mentally for Lesson 4's solution (free-threading).

Section 7: The 30-Year Design Tradeoff

Let's zoom out and see the bigger picture:

Why the GIL Made Sense in 1989

When Guido van Rossum created Python:

Hardware Reality:

- Single-core machines were standard

- No parallelism possible anyway

- Multi-threading was academic curiosity, not practical requirement

Design Benefits:

- Simple interpreter (no complex locking mechanisms)

- Easy C API (extension authors didn't need thread-safety expertise)

- Pragmatic for the era

Result: Python became extensible, practical, and adopted widely.

Why the GIL Became a Problem

Hardware Changed (1989 → 2024):

- Single-core → Multi-core standard

- Parallelism became expected

- Threading became practical necessity

GIL Consequences:

- Python threads can't leverage multi-core hardware

- Developer workarounds (multiprocessing, C extensions) are complex

- Python slower than Go, Rust, or Java for CPU-bound parallel work

How Free-Threading Solves It (Preview for Lesson 4)

Python 3.14 introduces free-threading—the GIL becomes optional:

Loading Python environment...

This solves the 30-year constraint. But how? By using biased reference counting and deferred reference counting:

- Biased RC: Most objects have single reference, don't need lock

- Deferred RC: Batch reference count updates, use cheaper synchronization

Result: Remove the global lock while maintaining thread safety. That's the innovation behind Lesson 4.

🎓 Expert Insight

Understanding the GIL means understanding technological constraints and their evolution. The GIL wasn't a mistake—it was the right call for 1989. The problem was that constraints which made sense for single-core machines became bottlenecks for multi-core machines 30 years later.

This is true for every technology: design choices optimal in one era become constraints in the next. The lesson: stay aware of why constraints exist, question them when circumstances change, and be ready to rethink fundamentals.

Free-threading is the rethinking of GIL fundamentals. Lesson 4 shows how.

Challenge 3: The GIL Impact Workshop

This challenge explores the GIL's consequences through hands-on experimentation and analysis.

Initial Exploration

Your Challenge: Experience the GIL's blocking firsthand.

Deliverable: Create /tmp/gil_discovery.py containing:

- CPU-bound task: calculate sum of squares for 50M numbers (takes ~3 seconds)

- Run sequentially: task 4 times (should be ~12 seconds)

- Run with

threading.Thread: 4 threads executing tasks (should still be ~12 seconds—GIL blocks parallelism) - Measure CPU utilization (one core only, not all 4)

- Compare to single-process (

multiprocessing.Process): should be ~3 seconds (true parallelism)

Expected Observation:

- Sequential: 12 seconds

- Threading: 12 seconds (GIL prevents parallelism)

- Multiprocessing: 3 seconds (true parallelism)

Self-Validation:

- Why doesn't threading help?

- Why does multiprocessing work?

- What's the difference at the implementation level?

Understanding GIL Constraints

💬 AI Colearning Prompt: "I ran 4 threads for CPU work and got zero speedup—it took the same time as sequential. But I have 4 CPU cores. Teach me: 1) What is the GIL and why does it exist? 2) Why can't Python just remove it? 3) When DOES threading help in Python? 4) What alternatives exist (multiprocessing, asyncio)? Show me the architecture of each."

What You'll Learn: GIL (memory safety mechanism), why it's hard to remove, when threading helps (I/O bound), and comparing solutions.

Clarifying Question: Deepen your understanding:

"You said the GIL protects reference counting from race conditions. But why not just use locks per object instead of a global lock? Wouldn't that allow parallelism?"

Expected Outcome: AI explains the tradeoff—fine-grained locks would be slower than global lock in practice. You learn about systems-level tradeoffs.

Exploring GIL Workarounds

Activity: Work with AI to test different GIL workarounds and understand their tradeoffs.

First, ask AI to show GIL workaround approaches:

"Show me 3 ways to work around the GIL: 1) Multiprocessing for CPU-bound work, 2) Asyncio for I/O-bound work, 3) C extensions (ctypes/cffi) that release the GIL. Code examples for each, showing speedup compared to threading. Explain when each workaround is appropriate."

Your Task:

- Run each approach. Measure speedup

- Identify issues:

- Multiprocessing: high overhead for small tasks

- Asyncio: only helps I/O, not CPU

- C extensions: require external dependencies

- Teach AI:

"Your multiprocessing example has 50% overhead—the setup cost eats speedup. How do I batch work to amortize overhead? When is multiprocessing worth it? For what task sizes?"

Your Edge Case Discovery: Ask AI:

"I have a hybrid workload: fetch data (I/O), process data (CPU), store results (I/O). Threading for I/O won't help CPU part (GIL blocks). Multiprocessing wastes resources. Should I use asyncio + executor? Show me the hybrid pattern."

Expected Outcome: You discover that workarounds have tradeoffs. No single solution fits all problems. You learn to choose based on workload characteristics.

Building a Concurrency Strategy Analyzer

Capstone Activity: Build a concurrency strategy recommendation system.

Specification:

- Analyze 5 workload types (CPU-heavy, I/O-heavy, hybrid, GPU-bound, memory-bound)

- For each workload, recommend concurrency strategy: threading, multiprocessing, asyncio, or hybrid

- Explain reasoning (GIL impact, overhead, scaling characteristics)

- Provide decision matrix:

{workload_type: (recommended_strategy, reasoning, expected_speedup)} - Include code template for each strategy

- Type hints throughout

Deliverable: Save to /tmp/concurrency_strategy.py

Testing Your Work:

python /tmp/concurrency_strategy.py

# Expected output:

# === Workload Analysis ===

# CPU-bound (50M calculation):

# Recommended: Multiprocessing (ProcessPoolExecutor)

# Reasoning: CPU-bound, GIL prevents threading parallelism

# Expected speedup: 3.5x on 4 cores

#

# I/O-bound (5 API calls, 1s each):

# Recommended: Asyncio (TaskGroup/gather)

# Reasoning: I/O-bound, asyncio allows concurrency, low overhead

# Expected speedup: 5x (concurrent vs sequential)

#

# Hybrid (fetch + process + store):

# Recommended: Asyncio + ProcessPoolExecutor

# Reasoning: Async I/O + parallel CPU work

# Expected speedup: 3x overall (limited by slowest stage)

Validation Checklist:

- Code runs without errors

- All 5 workloads have recommendations

- Reasoning explains GIL impact

- Speedup estimates are realistic

- Code templates are correct

- Type hints complete

- Could guide real project decisions

Time Estimate: 30-35 minutes (5 min discover, 8 min teach/learn, 8 min edge cases, 9-14 min build artifact)

Key Takeaway: The GIL isn't a bug to ignore—it's a constraint to understand. Different workloads need different solutions. Knowing when threading helps (I/O), when it fails (CPU), and what alternatives exist is essential for Python system design.

Try With AI

Why does threading speed up I/O-bound work but NOT CPU-bound work in CPython?

🔍 Explore GIL Mechanics:

"Show how the GIL works: create 2 threads doing CPU work (calculating primes). Measure total time vs single-threaded. Explain why you get NO speedup. What does the GIL prevent?"

🎯 Practice I/O vs CPU Workloads:

"Compare threading for: (1) downloading 5 URLs (I/O-bound), (2) calculating 5 large factorials (CPU-bound). Show timing results. Why does (1) speed up but (2) doesn't? Where does GIL release happen?"

🧪 Test GIL Release Points:

"Use threading with time.sleep() (releases GIL) vs tight loop (holds GIL). Show that sleep-based 'work' achieves concurrency but compute loops don't. Explain why I/O operations release GIL automatically."

🚀 Apply to Workload Classification:

"Given 5 workloads (web scraping, matrix multiplication, file I/O, API calls, data compression), classify each as I/O-bound or CPU-bound. For each, recommend: threading, multiprocessing, or asyncio. Justify with GIL constraints."