The $3 Trillion Developer Economy

Lesson Video:

Let's talk about money. Not because money is the only thing that matters, but because understanding the economic scale of what's being disrupted helps you grasp why this transformation is so significant.

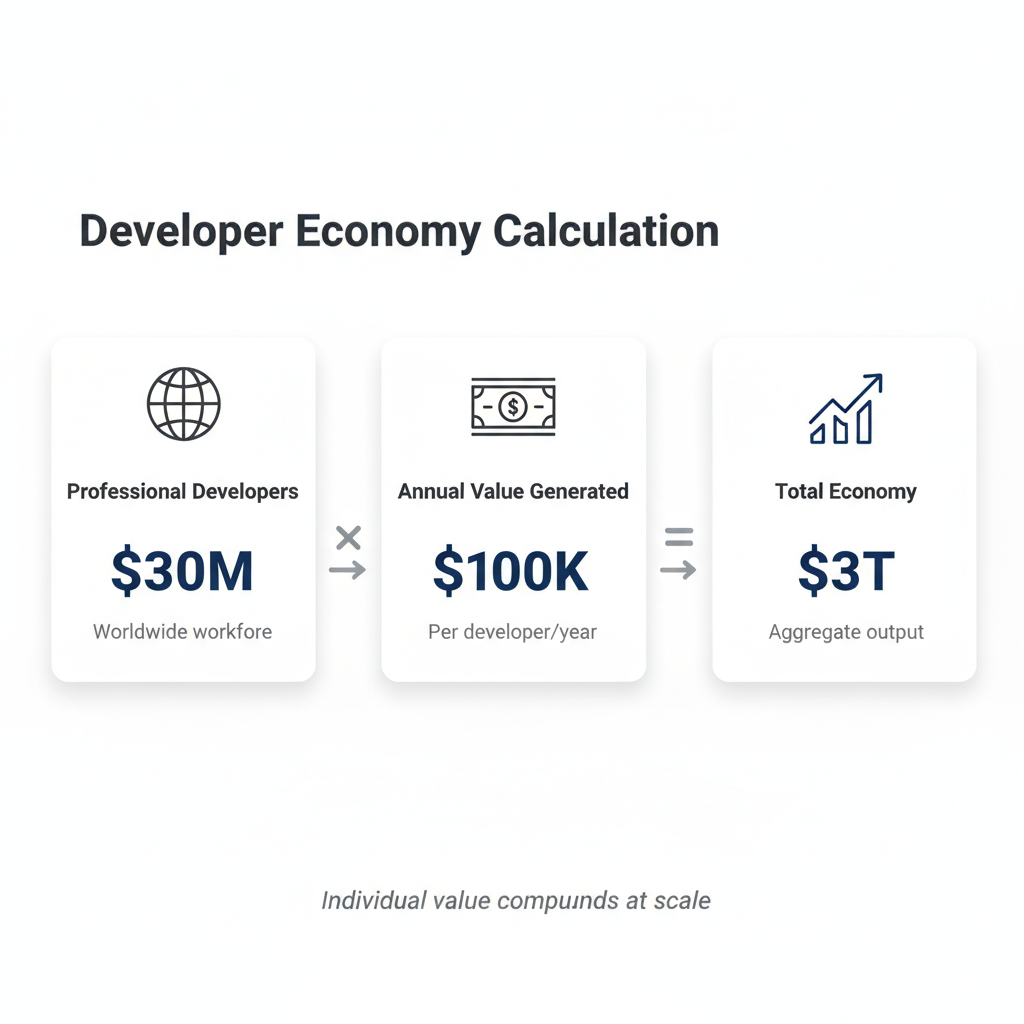

The Calculation

Here's the math, laid out transparently:

~30 million professional developers worldwide × $100,000 in annual generated value per developer = ~$3 trillion in aggregate economic output

Let's break down each component of this calculation to understand what it represents and why it's conservative.

30 Million Professional Developers

This figure comes from converging estimates across multiple sources:

- Evans Data Corporation's 2024 Worldwide Developer Population Report shows 27 million developers, with projections exceeding 30 million by 2025

- GitHub reports over 100 million developer accounts globally

- SlashData projects 45 million developers worldwide by 2030, indicating steady growth from current levels

- The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Eurostat, and equivalent agencies in major economies all point to similar global totals when aggregated

This number includes full-time software engineers, web developers, mobile developers, data engineers, DevOps specialists, and similar roles where coding is the primary job function. It does not include the growing population of "development-adjacent" professionals—designers who implement prototypes, product managers who write analysis scripts, technical writers who build documentation systems—which would push the total significantly higher.

$100,000 Generated Value Per Developer

This is the most controversial part of the calculation, so let's unpack it carefully.

We're not talking about developer salaries (which vary wildly by geography and seniority). We're talking about the economic value generated by a developer's work annually. This includes:

- Direct revenue from software products and services the developer builds

- Cost savings from automation and efficiency improvements

- Productivity gains for end users of the software

- Business enablement (new capabilities that unlock revenue streams)

In major tech companies, a single developer's annual output might generate millions in revenue. In smaller businesses, the figure might be tens of thousands. The $100,000 average accounts for this wide distribution.

Consider some reference points:

- A developer building e-commerce features for a mid-sized retailer might enable $5-10 million in annual online sales

- A developer maintaining critical infrastructure for a financial services company protects billions in transactions

- A developer building internal tools might save 100 employees 2 hours per week (10,000 hours annually), worth $500,000+ at typical knowledge worker rates

The $100,000 figure is actually conservative. Many industry analyses place the average economic impact per developer at $150,000-$200,000 annually.

💬 AI Colearning Prompt

Test your understanding: "If a developer's salary is $80K but they generate $100K+ in economic value, where does that extra value go? Ask your AI to explain the difference between salary and economic value generated."

Which Jobs Face Disruption? And Why?

Understanding the $3 trillion scale matters, but let's get specific: which jobs are affected by AI coding tools, and how deeply?

Research from OpenAI (as reported by David Rotman, Editor at Large for MIT Technology Review, in "ChatGPT is about to revolutionize the economy. We need to decide what that looks like," published March 25, 2023) provides concrete data:

- 80% of the workforce has some level of job exposure to AI tools

- 19% of workers are in jobs that will be heavily impacted

- Job categories most affected: writers, software developers, designers, financial analysts, blockchain engineers

Critical distinction: "Exposure" doesn't mean "elimination."

When researchers say 80% of jobs have "AI exposure," they mean AI tools can assist with at least some tasks in those roles. This is very different from saying "80% of jobs will be automated away."

The 19% "heavily impacted" category means jobs where AI tools can significantly assist with 30%+ of current tasks—not replace the entire job.

Why higher-income cognitive work is more vulnerable this time:

Previous automation waves (factory robots, ATMs, self-checkout) primarily affected physical labor and routine clerical work. AI coding tools are different: they target knowledge work—the exact jobs that were previously considered "automation-proof."

- A financial analyst writing Python scripts to analyze market data

- A designer prototyping interfaces in code

- A blockchain engineer implementing smart contracts

- A writer crafting technical documentation with embedded code examples

These roles involve cognitive work that, until recently, required years of specialized training. AI tools now compress that learning curve dramatically.

This doesn't mean these jobs disappear. It means the nature of the work shifts—from writing every line of code manually to designing systems, evaluating AI-generated solutions, and applying domain expertise that AI tools can't replicate.

What Does $3 Trillion Mean?

To put this in perspective:

$3 trillion is approximately the GDP of France—the world's 7th or 8th largest economy depending on exchange rates and measurement year.

It's roughly equivalent to:

- The entire GDP of India (population: 1.4 billion)

- 40% of China's annual economic output

- Double the GDP of Canada

In other words, if you think of the global developer workforce as a single economic entity, it would rank among the world's largest economies.

Why This Matters: Disruption at Scale

Now here's where it gets interesting—and why the Y Combinator data from the previous section isn't just an isolated trend.

A combination of AI startups (companies like Anthropic, OpenAI, GitHub, Replit, Cursor) and the underlying language models they've built are effectively disrupting an economy the size of a major nation.

And they're doing it fast.

Previous platform shifts in software development took 10-15 years to reach majority adoption:

- Personal computers (1980s): ~12 years from hobbyist machines to business standard

- The internet (1990s): ~10 years from academic network to commercial mainstream

- Cloud computing (2000s): ~15 years from AWS launch to cloud-first becoming default

- Mobile development (2010s): ~8 years from iPhone to mobile-first design being standard

AI coding tools are reaching similar adoption levels in less than 3 years:

- GitHub Copilot: launched October 2021, reached $100M ARR within approximately 2 years (October 2023)

- Claude Code: announced 2025, hit $500 million annualized revenue within two months

- Overall AI tool usage: 84% of developers using or planning to use AI tools, with 51% using them daily (Stack Overflow 2025 Developer Survey)

🎓 Expert Insight

This acceleration isn't just hype. Notice the pattern: PC revolution (12 years), Internet (10 years), Cloud (15 years), Mobile (8 years), AI coding (3 years). Each wave accelerates faster because infrastructure improves. Internet speeds, cloud platforms, and now LLM APIs enable rapid adoption. You're entering during the fastest technology transition in software history.

Two Economic Futures: The Outcome Isn't Predetermined

Here's the critical question: Does this transformation lead to widespread prosperity or concentrated inequality?

The answer isn't determined by the technology itself. As MIT Technology Review's David Rotman emphasizes: "We need to decide what that looks like."

Economists Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, in their framework "Power & Progress," show that technology's impact depends on societal choices—not technological inevitability.

The Optimistic Future: AI as an Upskilling Tool

In this scenario, AI tools democratize software development, lowering barriers to entry and expanding opportunity:

-

Evidence from research: A MIT productivity study by researchers Shakked Noy and Whitney Zhang found that ChatGPT helped the least-skilled workers improve the most—exactly the pattern you'd expect from a democratizing technology.

-

What this looks like: Domain experts (doctors, teachers, scientists) build custom tools for their fields without needing traditional CS degrees. Small businesses create bespoke software that was previously too expensive. The "developer" population expands from 30 million to potentially hundreds of millions.

-

Economic pattern: Similar to the post-World War II era, when technological advancement (electrification, mass production) combined with broad-based institutional support led to widely shared prosperity.

The Pessimistic Future: AI as an Inequality Accelerator

In this scenario, AI tools primarily benefit those who already have resources and access:

-

The risk: If AI coding tools remain proprietary, expensive, or require elite training to use effectively, they could concentrate wealth rather than distribute it.

-

What this looks like: Large tech companies capture most value from AI productivity gains. Displaced workers lack pathways to transition into AI-augmented roles. The gap between AI-skilled and non-AI-skilled workers widens dramatically.

-

Economic pattern: Similar to recent decades, where automation and globalization increased productivity but concentrated gains among capital owners and highly skilled workers, leaving many middle-income workers behind.

Which Future Are We Heading Toward?

AI TOOLS EMERGE (2023-2025)

|

|

┌──────────▼──────────┐

│ DECISION POINT │

│ How do we design │

│ and deploy AI? │

└──────────┬──────────┘

|

┌────────────────┴────────────────┐

| |

▼ ▼

┌─────────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────┐

│ OPTIMISTIC FUTURE │ │ PESSIMISTIC FUTURE │

│ │ │ │

│ • Broad access │ │ • Restricted access │

│ • Upskilling │ │ • Replacement │

│ • Democratization │ │ • Displacement │

│ • Shared prosperity │ │ • Concentrated │

│ │ │ wealth │

│ Evidence: MIT study │ │ Risk: Historical │

│ shows least-skilled │ │ pattern of recent │

│ gain most │ │ decades │

└─────────────────────┘ └─────────────────────┘

↑ ↑

| |

EXPANSION POLARIZATION

The answer depends on choices being made right now:

-

Access to tools: Are AI coding assistants becoming widely available (like open-source models and affordable commercial tools)? Or restricted to those with resources?

-

Education systems: Are schools teaching AI-augmented development, or clinging to pre-AI curricula?

-

Policy decisions: Are governments investing in transition support, or leaving displaced workers to navigate change alone?

-

Your choices: Are you positioning yourself to partner with AI (learning judgment, design, domain expertise), or compete with AI (learning what AI already excels at)?

The transformation is happening regardless. But which version of the transformation we get isn't predetermined by technology—it's shaped by millions of individual and collective decisions.

The Acceleration Paradox

Here's something that surprised economists and industry analysts: AI coding tools are accelerating software production, not reducing it.

Traditional economic logic suggested that automation reduces demand for labor. If machines can code, you'd need fewer developers, right?

Wrong.

What's actually happening is more subtle and more profound:

From Software-as-a-Service to Software-as-Craft

For the past two decades, software followed a SaaS model: build one application, serve thousands or millions of users. This made economic sense because software was expensive to create. You needed to amortize development costs across many customers to justify the investment.

AI coding tools are enabling a shift toward highly customized, individual software solutions—what some industry observers call "vibe coding." Because the cost and time to create software have dropped dramatically, individuals can now build bespoke applications tailored to their specific workflows, preferences, and requirements.

The YC founders with 95% AI-generated codebases aren't building generic SaaS products for mass markets. They're creating specialized solutions for specific niches, custom-tailored to particular business models and user needs. Because AI tools make it feasible to build sophisticated systems in days instead of months, founders can afford to create highly targeted solutions.

This doesn't shrink the software market. It explodes it.

The Developer Population Is Growing, Not Shrinking

Paradoxically, as AI tools become more powerful, the number of people who identify as developers is increasing:

-

Domain experts (healthcare professionals, financial analysts, scientists) are writing code to solve problems in their fields, enabled by AI assistants that handle syntax and implementation details

-

Creative professionals (designers, writers, artists) are building interactive experiences and generative tools

-

Entrepreneurs and founders are prototyping and launching products without hiring full development teams

The traditional gatekeepers to programming—memorizing syntax, understanding low-level implementation details, mastering complex toolchains—have been removed. The result is democratization, not displacement.

Evidence from MIT research reinforces this optimistic view: In a controlled study, MIT researchers Shakked Noy and Whitney Zhang tested ChatGPT's impact on professional writers completing realistic tasks. They found that ChatGPT improved productivity across all skill levels, but the biggest gains went to the least-skilled workers—those who previously struggled most with the tasks.

This is exactly the pattern you'd expect from a democratizing technology, not a displacement technology. If AI were simply replacing workers, you'd see the opposite: high-skilled workers maintaining their advantage while low-skilled workers fell further behind. Instead, AI tools are raising the floor—bringing more people into capability ranges that were previously restricted to experts.

The same pattern is emerging in software development: beginners with domain expertise (a scientist who knows biology but not Python, a teacher who understands pedagogy but not databases) can now build functional tools that solve real problems.

🎓 Expert Insight

AI doesn't shrink the developer market. It expands who can be a developer. Think about spreadsheets: they didn't eliminate accountants. They made financial analysis accessible to everyone, expanding the field. Same pattern here. Lower barriers mean more builders, not fewer.

The Turing Trap: Replacement vs. Augmentation

But here's a critical distinction that determines whether you thrive in this transformation or struggle through it:

The "Turing Trap"—a concept from MIT economist Erik Brynjolfsson—describes what happens when we build AI to mimic humans rather than amplify them.

When AI is designed to replicate what humans already do (write code line-by-line, debug syntax errors, implement standard algorithms), the inevitable result is replacement: humans competing with machines for the same tasks. This leads to downward pressure on wages and reduced job opportunities for those whose skills overlap with AI capabilities.

But there's an alternative: augmentation—designing AI to enhance human capabilities rather than substitute for them.

Positioning Yourself: Partner or Competitor?

This isn't an abstract policy debate. It's a personal decision you're making every time you choose what to learn:

Competing with AI means learning:

- Syntax and language-specific details (AI excels at this)

- Implementing standard patterns and boilerplate (AI generates this instantly)

- Memorizing API documentation (AI has perfect recall)

- Writing routine CRUD operations (AI does this faster)

Partnering with AI means learning:

- System design and architecture (understanding how components should fit together)

- Domain expertise (knowing what problem you're actually solving)

- Judgment and evaluation (recognizing when AI-generated code is correct vs. subtly wrong)

- Creative problem-solving (finding novel approaches AI hasn't been trained on)

- Human context (understanding user needs, business constraints, ethical implications)

The lesson here isn't "don't learn to code." It's "learn to code differently"—focus on the skills that make you AI's partner, not its replacement.

Historical Precedent: When Industries Disrupted Themselves

Software disrupting itself has few direct historical parallels, but one comparison stands out:

The printing industry in the late 20th century.

For centuries, printing required specialized craftspeople—typesetters, pressmen, bindery workers—with years of training. The introduction of desktop publishing software (PageMaker, QuarkXPress, and later Adobe InDesign) automated many of these specialized skills.

What happened? The number of printing professionals didn't collapse. Instead, the nature of the profession transformed. Graphic designers absorbed typesetting skills. Print shops became creative agencies. The barrier to professional-quality publishing dropped, and the total volume of printed material exploded.

The $3 trillion developer economy is undergoing a similar transformation—but faster, and at larger scale.

Why History Suggests Two Futures Are Possible

Looking deeper at historical precedent, economists Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson (in their framework "Power & Progress") show that technology's impact on workers has never been automatic—it has always depended on institutional choices and power dynamics.

Post-World War II era (1945-1975): Technology advanced rapidly (automation, computers, telecommunications), yet this period saw widely shared prosperity:

- Productivity gains translated to wage growth across income levels

- Strong unions, progressive taxation, and social programs ensured broad benefit

- Technology complemented workers rather than replacing them

- The middle class expanded even as automation increased

Recent decades (1980-present): Similar technological advancement (computers, internet, automation), but vastly different outcomes:

- Productivity continued rising, but wages for most workers stagnated

- Gains concentrated among capital owners and highly educated workers

- Weakened institutions meant workers captured less of the value they created

- Automation often replaced rather than augmented workers

The difference wasn't the technology—it was the institutional structures, policy choices, and power relationships that determined how technological gains were distributed.

This is why the "Two Economic Futures" framework matters: AI's impact on the developer economy isn't predetermined by algorithms and models. It will be shaped by choices about access, education, policy, and how we design these systems.

What This Means For You

Whether you're a beginner, an experienced developer, or an educator, understanding the scale of this transformation matters because:

-

This isn't a niche trend. When an economy the size of France's GDP is being restructured, everyone in the industry is affected. There's no "waiting it out."

-

The opportunity window is open right now. Early adopters of previous platform shifts (PC, internet, cloud, mobile) captured disproportionate value. We're still in the early phase of the AI coding revolution.

-

Traditional assumptions are breaking down. "Learn to code the hard way," "You need a CS degree," "Start with syntax and algorithms"—these mantras made sense in 2020. They're actively harmful in 2025.

-

The skills that matter are changing. If you're learning what AI tools are best at (syntax, boilerplate, standard patterns), you're competing with automation. If you're learning what humans uniquely provide (judgment, creativity, domain expertise, system design), you're positioning yourself for the transformed landscape.

-

Your choices shape which future emerges. Every time you choose to learn AI-augmented development (rather than avoiding AI), support accessible AI tools (rather than proprietary lock-in), or help others transition (rather than hoarding knowledge), you're nudging the economy toward the optimistic future. Individual choices aggregate into collective outcomes.

🤝 Practice Exercise

Ask your AI: "The lesson claims AI is expanding the developer market, not shrinking it. Help me understand why this is true using one concrete example from history (like spreadsheets and accountants, or calculators and mathematicians). Then explain how this applies to my learning path."

What you're practicing: Understanding market dynamics and positioning yourself in an expanding field, not a shrinking one.

In the next section, we'll explore why this particular disruption—software disrupting itself—is fundamentally different from previous technology shifts, and why it's happening so fast.

Video Resource:

Want to see the original analysis that inspired this chapter? Watch the full presentation:

This 40-minute presentation from industry analysts provides the detailed evidence and case studies behind the $3 trillion figure, along with projections for where the market is heading.

Try With AI

Use your AI companion tool set up (e.g., ChatGPT web, Claude Code, Gemini CLI), you may use that instead—the prompts are the same.

Prompt 1: Understand The Economic Scale

This lesson talks about a '$3 trillion developer economy.' Explain this in simple terms—what does it actually mean, and why should I care? Is this number real or inflated? Help me understand the scale we're talking about using comparisons I can relate to (like country GDPs or familiar industries).

Expected outcome: Clear grasp of the economic scale (without needing an economics degree).

Prompt 2: Personal Impact Assessment

The lesson says AI is 'disrupting an economy the size of France.' But how does that affect me personally? If I'm [your role: student / entrepreneur / career changer / business owner], what does this transformation mean for my opportunities? Be specific about how I might benefit.

Expected outcome: Personal understanding of how this transformation creates opportunities for YOU.

Prompt 3: Clarify The Productivity Paradox

Here's what confuses me: If AI makes developers more productive, won't we need FEWER developers? Help me understand why the lesson claims the opposite—that demand for software is actually INCREASING. Use a simple analogy or real example I can grasp.

Expected outcome: Insight into why AI expands rather than shrinks the software market.

Prompt 4: Strategic Direction Planning

Based on this economic shift, help me think strategically: Should I focus on learning to build custom solutions for specific needs? Or should I aim for building products that serve many people? What's more realistic for someone starting with AI tools in 2025?

Expected outcome: Strategic guidance on where to focus your learning efforts.

Prompt 5: Two Futures Positioning

The lesson describes two possible economic futures from AI: optimistic (widespread opportunity) vs. pessimistic (concentrated inequality). Which future appeals to you more, and why? Ask your AI to help you think through: What would you need to do differently if the optimistic future emerged? What about the pessimistic one? How does your answer change your learning priorities right now?

Expected outcome: Clarity on how different scenarios affect your personal strategy and what actions align with your preferred future.

Prompt 6: Augmentation vs. Competition

Ask your AI to give you examples of positioning yourself as AI's partner vs. AI's competitor in software development. What specific skills make you compete with AI (things AI is already good at) vs. partner with AI (things humans uniquely provide)? Based on this, what should you focus on learning first?

Expected outcome: Concrete understanding of which skills to prioritize to position yourself for AI-augmented development (partner) rather than competing with automation.

Prompt 7: Evidence-Based Career Confidence

Pick ONE research finding from this lesson: (1) OpenAI's job exposure study, (2) MIT's productivity study showing ChatGPT helped least-skilled workers most, or (3) Acemoglu/Johnson's historical examples of technology outcomes depending on choices. Ask your AI to help you explain to a skeptic why this specific evidence shows AI is expanding, not shrinking, the developer field. Practice making an evidence-based argument.

Expected outcome: Ability to cite specific research to counter the "AI will eliminate developer jobs" narrative with concrete evidence.